Things aren’t looking good for NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS). Occasionally referred to as the “Senate Launch System”, or even less graciously, the “Rocket to Nowhere”, the super heavy-lift booster has long been a bone of contention for those in the industry. Designed as an evolution of core Space Shuttle technology, the SLS promised to reuse existing infrastructure to deliver higher payload capacities and lower operating costs than its infamous winged predecessor. But in the face of increased competition from commercial launch providers and proposed budget cuts targeting future upgrades and expansions of the core booster, the significantly over budget and behind schedule program is in a very precarious position.

Which is not to say the SLS doesn’t look impressive, at least on paper. In its initial configuration it would easily take the title as the world’s most powerful rocket, capable of lifting nearly 105 tons into low Earth orbit (LEO), compared to 70 tons for SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. It would still fall short of the mighty Saturn V’s 155 tons to LEO, but the proposed “Block 2” upgrades would increase SLS payload capability to within striking distance of the iconic Apollo-era booster at 145 tons. Since the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA has been adamant that the might of SLS was the only way the agency could accomplish bigger and more ambitious missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Which is not to say the SLS doesn’t look impressive, at least on paper. In its initial configuration it would easily take the title as the world’s most powerful rocket, capable of lifting nearly 105 tons into low Earth orbit (LEO), compared to 70 tons for SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. It would still fall short of the mighty Saturn V’s 155 tons to LEO, but the proposed “Block 2” upgrades would increase SLS payload capability to within striking distance of the iconic Apollo-era booster at 145 tons. Since the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA has been adamant that the might of SLS was the only way the agency could accomplish bigger and more ambitious missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Or at least, they were. On March 13th, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine testified to Congress that in an effort to avoid further delays, the agency is exploring the possibility of sending their Orion spacecraft to the Moon with a commercial launcher. The statement came as a shock to many in the aerospace community, as it would seem to call into question the future of the entire SLS program. If commercial rockets can do the job of SLS, at least in some cases, why does the agency need it?

NASA is currently preparing a report which investigates what physical and logistical modifications would need to be made to missions originally slated to fly on SLS; a document which is sure to be scrutinized by SLS supporters and critics alike. Until the report is released, we can speculate about what this hypothetical flight to the Moon might look like.

A Drop in Replacement

Administrator Bridenstine didn’t specifically mention which commercial vehicle they were looking at during his Congressional testimony, but as the Falcon Heavy has the highest payload capacity of any currently operating launch platform, it would almost certainly be the focus of NASA’s report. It might seem like the considerably lower capacity of the Falcon Heavy would be a problem, but in reality, Orion’s proposed test flight to the Moon was never going to fully utilize the capability of the SLS to begin with.

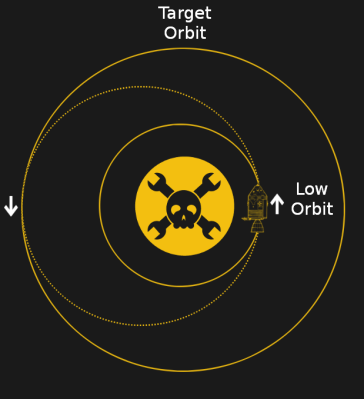

During “Exploration Mission 1”, the SLS is only responsible for getting the Orion, its Service Module, and the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) into orbit around the Earth; it actually separates from the spacecraft at an altitude of just 157 kilometers. From that point on, Orion operates independently, and the ICPS is what actually propels the craft towards the Moon.

The Orion and Service Module together weigh in at around 57,000 lbs, and the ICPS itself tips the scales at roughly 66,000 lbs. So at least in theory, any booster that can lift around 125,000 lbs into orbit should be able to stand in for the SLS on this first mission. That’s well within the capabilities of the Falcon Heavy, even if we assume a few thousand extra pounds for ancillary hardware and whatever adapters it would take to bolt everything together. A new fairing would need to be designed and manufactured to encapsulate such a large payload, but all things considered, it seems like it would be a fairly straightforward process.

Taking the Falcon Express

Interestingly, some quick back of the envelope math seems to indicate there’s another option on the table. Assuming NASA is willing to make some substantial deviations from the original mission parameters, it looks like the Falcon Heavy alone could potentially push the Orion most of the way towards the Moon itself without using the ICPS at all. This would not only make it easier to integrate the Orion hardware onto the Falcon Heavy, but would save the non-reusable ICPS for a future mission.

According to SpaceX, the Falcon Heavy is capable of lifting a bit more than 58,000 lbs into a geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). As you may recall our last lesson in “Beginner’s Orbital Mechanics”, a GTO orbit is the first half of an orbital transfer from a low Earth orbit to the geosynchronous equatorial orbit (GEO) altitude of 35,786 kilometers. Once the spacecraft has been placed into GTO by the Falcon’s upper stage, onboard propulsion would raise its perigee to circularize the orbit and complete the transfer.

According to SpaceX, the Falcon Heavy is capable of lifting a bit more than 58,000 lbs into a geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). As you may recall our last lesson in “Beginner’s Orbital Mechanics”, a GTO orbit is the first half of an orbital transfer from a low Earth orbit to the geosynchronous equatorial orbit (GEO) altitude of 35,786 kilometers. Once the spacecraft has been placed into GTO by the Falcon’s upper stage, onboard propulsion would raise its perigee to circularize the orbit and complete the transfer.

This means the Falcon Heavy should just be able to put the Orion and its Service Module into GTO. Of course that doesn’t get you to the Moon, but it’s not quite that far off either. To reach GTO from Earth orbit, a spacecraft must increase its velocity by roughly 2.5 kilometers per second. By comparison, for lunar injection it needs to be accelerated by around 3.2 km/s. So how do we get the last 700 meters per second of acceleration? From the Orion itself.

As per the design specifications, the Orion Service Module is able to provide 1.8 km/s of delta-v. In theory, it should be able to complete the trans-lunar injection maneuver with enough propellant in reserve to perform any necessary course corrections. In this theoretical scenario, there may not be enough propellant to actually slow down and enter a lunar orbit as originally intended. In which case, Orion could simply make a loop around the far side of the Moon and then return to Earth. This “free return” flight path was previously used as a contingency for the early Apollo missions; had the spacecraft been unable to perform the lunar orbit insertion maneuver, it would have allowed the crew to essentially “drift” home.

NASA Plays it Safe

These are interesting thought experiments, but unfortunately, the reality is likely to be quite a bit less exciting. Some believe that the statements made to Congress were essentially a threat directed at Boeing, the prime contractor on the Space Launch System. A not so subtle signal that the agency is getting tired of the delays and cost overruns. Indeed, just two days after his testimony, Administrator Bridenstine Tweeted that Boeing teams were working to accelerate the SLS timetable.

Even if the Orion does fly on a commercial rocket, Administrator Bridenstine said the agency believes the mission would best be served by utilizing two launches and assembling the spacecraft in orbit. Until the final report is released, it’s unclear why NASA would select such a complicated path to the Moon. Especially considering that the Orion currently has no provision for orbital assembly, and this technology would have to be integrated into the vehicle on exceptionally short notice to meet the planned launch date of June 2020.

If we’ll allow one last bit of conspiracy theory, some in the community have put forward the idea that NASA is proposing the most expensive and complex possible way to launch Orion on a commercial rocket to help bolster the idea that the SLS is indispensable. If the world sees Orion’s Exploration Mission 1 completed on the back of just a single Falcon Heavy, at 1/10th the cost of flying on the SLS, it would arguably be more humiliating for the agency than simply scrapping the mission entirely.

https://hackaday.com/2019/03/25/could-orion-ride-falcon-heavy-to-the-moon/

2019-03-25 14:00:00Z

52780250160084

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar