In the early morning hours on Wednesday, we have a chance to see bright streaks across the sky, thanks to Halley's Comet and the eta Aquariid meteor shower.

Comet Halley is probably the most well-known comet in the world. It puts on a spectacular show every time it flies past our planet, but it only does so once every 75 years.

Twice each year, though, we get a reminder from 1P/Halley that it's only a matter of time before it comes back for another pass. The first such reminder arrives in the first week of May, in the form of bright streaks of light across the night sky.

This is the eta Aquariid meteor shower, which peaks on the night of May 5-6.

The radiant of the eta Aquariid meteor shower, in the hours before dawn, on May 6. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The radiant of the eta Aquariid meteor shower, in the hours before dawn, on May 6. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

It's at this time of the year when Earth is making its first pass through the trail of dust and ice left behind by 1P/Halley, as it swings through the inner solar system and around the Sun. The peak of the meteor shower, typically seen in the morning hours of May 6, is when we cross the densest part of that stream. The planet makes a second pass through Halley's debris trail in late October, producing the Orionids meteor shower at that time.

WILL WE SEE IT?

The best time to see the eta Aquariids is in the few hours just before dawn on May 6. The radiant - the point in the sky where the meteors appear to originate from - only rises above the eastern horizon at around 3 a.m., local time.

This year is not ideal for the eta Aquariids, due to how soon dawn arrives after the radiant rises, and due to the presence of a nearly Full Moon in the sky. Fortunately, with the Moon in the southwestern part of the sky as the radiant rises in the east, its bright light will not be directly in a viewer's eyes. The light it does cast will 'wash out' the dimmest meteors from the shower, though.

Sky conditions will also be an important factor. Check your cloud forecast for the early morning, to see if your skies will be clear enough.

If it is cloudy where you are, thus blocking your view of the meteor shower, there are other ways to check it out.

You can see the signal meteoroids make when they plunge into the atmosphere via Meteor Radar or listen to them via the Meteor Echoes Livestream.

Astronomy Live Stream also presents nightly views of the sky over Colorado.

WHAT CAN WE SEE?

The eta Aquariids typically produce around 50 meteors per hour under ideal conditions (clear, dark sky, with the meteor shower radiant directly overhead). Most observers will likely see about half that number, so around 20-25 per hour, under this year's conditions.

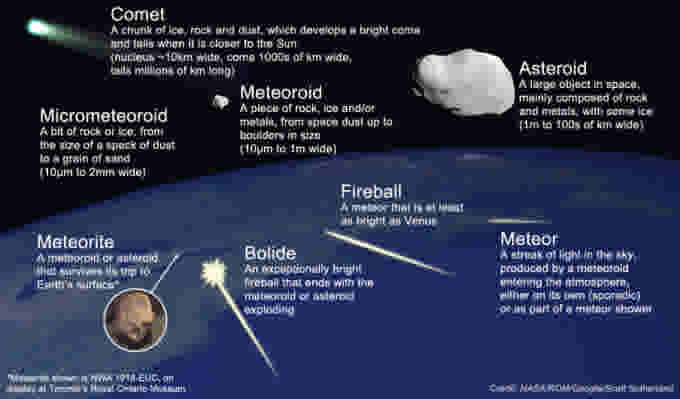

The flash of a meteor is the result of one of those bits of dust or ice from the comet debris trail hitting the top of Earth's atmosphere.

A primer on meteoroids, meteors and meteorites. Credits: Scott Sutherland/NASA JPL (Asteroids Ida & Dactyl)/NASA Earth Observatory (Blue Marble)

A primer on meteoroids, meteors and meteorites. Credits: Scott Sutherland/NASA JPL (Asteroids Ida & Dactyl)/NASA Earth Observatory (Blue Marble)

When a typical 'meteoroid' hits the top of the atmosphere, it is travelling around a hundred thousand kilometres per hour. It very quickly compresses the air in its path, so much so that the air heats up to glow, white-hot! This glowing is the 'meteor' that we see streaking through the air, high above the ground.

All the while, the air is pressing back on the meteoroid, causing it to slow down, and sometimes exerting enough force on the meteoroid to shatter it! Once the meteoroid slows to the point where it can no longer heat the air to the point of glowing, the meteor winks out.

This eta Aquariids meteor shower does not tend to produce bright fireballs, as the Lyrids do. The meteoroids are moving so quickly when they hit our atmosphere, however, that they can produce a phenomenon called persistent trains.

'PERSISTENT TRAINS'??

Watch below to see a persistent train from the Geminid meteor shower

When a typical cometary meteoroid hits the top of Earth's atmosphere, it is moving fast enough to produce a meteor flash (as mentioned above). The particles in the eta Aquariid stream, however, hit Earth's atmosphere travelling at nearly two and a half times faster than average!

Streaking through the air at 240,000 km/h, meteoroids from Comet Halley produce the usual brief meteor flash. They can also result in a bonus. Once the meteor goes out, a glowing trail is left behind, floating in the air, called a persistent train. Some persistent trains last for minutes after the meteor flash, while others remain visible for hours.

Since persistent trains have only rarely been recorded, scientists still aren't quite sure what causes them. Two basic ideas could explain them, though.

The first is that the meteoroids are travelling fast enough to strip electrons from the air molecules, leaving them in an ionized state. As the air molecules snatch up electrons from their surroundings, they release energy in the form of light. Since this process can take much longer than the original meteor flash, the 'train' appears fainter, and it can persist for some time after the meteor flash ends.

The other idea involves what is known as 'chemiluminescence'. Metals vaporizing off the surface of the fast-moving meteoroids can chemically react with ozone and oxygen in the air, to produce a glow.

One of these explanations may account for these 'trains', or both may cover different occurrences, at different times, and even between individual meteors. It will take more sightings of these to explain them fully.

Sources: RASC | Spaceweather

WATCH BELOW: METEORS SPOTTED FROM THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMicGh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnRoZXdlYXRoZXJuZXR3b3JrLmNvbS9jYS9uZXdzL2FydGljbGUvaG93LXRvLXdhdGNoLXRoZS0yMDIwLWV0YS1hcXVhcmlpZC1tZXRlb3Itc2hvd2VyLWZyb20tYW55d2hlcmXSAQA?oc=5

2020-05-05 17:20:00Z

52780756999316

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar