Watch live coverage on CBSN Wednesday, May 27. Launch is scheduled for 4:33 p.m. EDT.

Opening a new chapter in American spaceflight, two veteran space shuttle fliers will blaze a fresh trail to orbit aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft Wednesday, weather permitting — the first launch of American astronauts from U.S. soil since the space shuttle's final flight nearly nine years ago.

The historic mission, the first orbital flight of a new piloted spacecraft in 39 years, is the culmination of a six-year, multibillion-dollar NASA drive to end the agency's sole reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for transportation to and from the space station.

The government-financed, privately owned and operated astronaut ferry ships will enable NASA to expand the space station's crew to seven, including four full-time NASA and partner agency astronauts, maximizing the amount of research that can be carried out in the $100 billion lab complex.

The mission, known as Demonstration Test Flight No. 2 — Demo 2 — will mark the second launch of a SpaceX Crew Dragon and the first with astronauts on board. If no major problems are found, the agency is expected to certify the spacecraft for operational space station crew rotation missions, clearing the way for launch of a three-man, one-woman crew this fall.

Longer term, NASA also expects the Commercial Crew Program, under which SpaceX and, eventually, Boeing, will launch private citizens as well as professional astronauts, to open up the high frontier to private sector development, including privately operated space stations.

"This is a new generation, a new era in human spaceflight," said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. "NASA has long had this idea that we need to build, own and operate hardware to get to space. And in the past that has been true.

"But now in this new era, NASA, especially in low-Earth orbit, has an ability to be a customer, one customer of many customers in a very robust commercial marketplace. ... We want to have numerous providers that are competing against each other on cost and innovation. And that's really what we are entering into with this new era of human spaceflight."

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic and agency-wide workforce restrictions, Crew Dragon commander Douglas Hurley, the pilot of the final shuttle mission in July 2011, and crewmate Robert Behnken flew to the Kennedy Space Center this past Wednesday to begin final preparations.

They looked on Friday as SpaceX test fired the their booster's nine first-stage engines, then donned their spacesuits and strapped in Saturday for a dress rehearsal countdown. If all goes well, they will blast off Wednesday at 4:33:33 p.m. EDT and dock with the International Space Station at 11:40 a.m. the next day.

"It's tremendously exciting to be where we are, on the cusp of launching a commercial crew vehicle," Hurley told Vice President Mike Pence during a video chat last week with the National Space Council. "It's an exciting time to be in the space business. ... I almost wish I was a young astronaut again because it's going to be an exciting time for folks who fly in space."

Pandemic limits public viewing

NASA normally would expect enormous crowds across Florida's "Space Coast" to share that excitement, especially for the first such flight in nearly a decade. But the Kennedy Space Center remains closed to non-essential personnel, part of NASA's agency-wide response to the coronavirus pandemic.

And so, for the first time in its history, NASA will not open the space center for public launch viewing and has sharply limited the number of journalists on site while implementing strict social distancing protocols.

"The challenge that we're up against right now is we want to keep everybody safe," Bridenstine said. "That's the number one, highest priority of NASA, keeping people safe. And so we're asking people not to travel to the Kennedy Space Center.

"We don't want an outbreak. We need a spectacular moment that all of America can see and all of the world can see to inspire not just those of us who've been waiting years for this, but to inspire the generations that are coming. And we need to do it in a way that's responsible.

"So we're asking people not to travel to Kennedy but to watch on line or watch on your television at home. ... But we're asking people not to make the trip to Kennedy."

That includes the crew's extended families and friends. Instead of being able to invite hundreds of guests to share the excitement of launch, the usual NASA practice, Hurley's wife, veteran astronaut Karen Nyberg, and fellow astronaut Megan McArthur, Behnken's wife, were limited to just 15 guests each.

"We were looking forward to celebrating with lots of people who could physically come to the Cape and enjoy watching the launch in person," McArthur said. "But I have gotten so many notes of support from people all over the country saying hey, we're still going to be with you, we're going to be watching from home, but we're still cheering Bob and Doug on, you know — go, Dragon! — and so people are still really, really excited about it."

Hurley and Nyberg have one son, 10-year-old Jack, as do Behnken and McArthur, 6-year-old Theodore.

"One good thing for us, the positive side, is that our sons have been basically quarantined from other children for two months," said Nyberg. "So they do get a little extra time with their dads closer to launch, which is nice."

The immediate families plan to watch the launch from the roof of NASA's Launch Control Center just 3.2 miles from pad 39A.

Dragon launch may be "smoother" but "louder"

Launching directly into the plane of the space station's orbit, the Falcon 9 will climb away on a northeasterly trajectory atop 1.7 million pounds of thrust from its first stage engines.

As has become commonplace with SpaceX, the rocket's first stage, after powering the spacecraft out of the thick lower atmosphere, will attempt to land on an off-shore droneship while the second stage continues the climb to orbit. Twelve minutes after liftoff, the Crew Dragon will be released to fly on its own.

"Based on our shuttle experience, the first stage was pretty rough and rumbly as well from a noise perspective," Behnken said. "We expect Dragon to kind of be a little bit of both. We expect it to be smoother, but we also expect it to be louder (during) that initial portion of the launch."

Throughout their trip to the space station, Hurley and Behnken will communicate with flight controllers through engineers at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California, not traditional "capsule communicators," or CAPCOMs, in mission control at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Instead, a SpaceX employee, known as a "crew operations responsible engineer," or CORE, will relay instructions to the astronauts, answer questions, provide flight plan updates and generally serve as the crew's interface with the SpaceX control team overseeing Crew Dragon operations from company headquarters in Hawthorne, California.

Once Hurley and Behnken begin their final approach to the station, NASA CAPCOMs and flight directors will resume their traditional roles, coordinating rendezvous procedures and closely monitoring the final stages of the docking procedure.

Described as a "flying iPhone," the highly automated spacecraft, equipped with large state-of-the-art touch-screen displays in its futuristic cockpit, is designed to execute a fully autonomous rendezvous and docking.

But for this initial test flight, Hurley and Behnken plan to take the controls and "fly" the capsule to test their ability to manually maneuver shortly after reaching orbit and again during final approach to the station.

Asked to compare the Crew Dragon to the much larger, much more complex -- and expensive -- space shuttle, Hurley said "what's not to like? It's a flying vehicle. It's a spaceship. And we're going to get to fly it."

Weather constraints – and an escape system

In a major departure from past U.S. launch systems, the Crew Dragon is equipped with a "full envelope" abort system capable of blasting the capsule safely away from its booster at any point from the launch pad to orbit if a major malfunction is detected. The capsule also is capable of carrying out an emergency return from orbit.

NASA's single-seat Mercury and three-seat Apollo capsules were equipped with solid-propellant rockets to pull the capsule away during the initial stages of launch. Two-man Gemini capsules relied on ejection seats.

The Crew Dragon is equipped with eight liquid-propellant SuperDraco engines, capable of pushing the capsule a half mile away from the Falcon 9 in 7.5 seconds. The abort system was successfully tested during a January flight, accelerating an unpiloted Crew Dragon to 400 mph relative to the rocket.

Hurley said the abort system, and the capsule design, make Crew Dragon intrinsically safer than the space shuttle. The space shuttle had a record of two catastrophic failures in 135 flights, putting the demonstrated odds at just under 1-in-70. The commercial crew program risk assessment calls for a 1-in-270 chance of a vehicle-related in-flight fatality.

"This vehicle has end-to-end abort capability, on the pad all the way up to orbit," Hurley said. "And so that perspective for me is huge compared to shuttle where there were what we call 'black zones' where it didn't really matter if you had the right combination of failures, you were likely not going to survive an abort."

When Behnken told his 6-year-old son that he would be flying on the Crew Dragon, "the only question he had was whether or not the Dragon was going to roar." He showed his son it would, in fact, roar with a visit to the space center to take in a Dragon cargo launch.

"We've done everything we can, and so have the folks (at SpaceX), to make sure that the Dragon isn't gonna bite us," Behnken said. "And if it tries, there's an escape system that's going to help us get away from the Falcon."

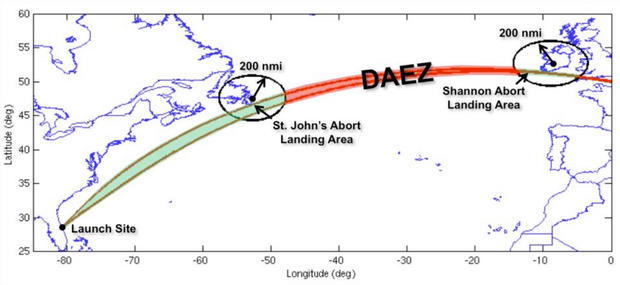

But depending on when an abort might be executed, Hurley and Behnken could be forced to splash down at any point along a trajectory stretching from Cape Canaveral to the North Atlantic Ocean off Newfoundland or, on the other side of an "exclusion" zone, near the coast of Ireland.

Air Force helicopters, two C-130 aircraft, a C-17 jet and teams of parajumpers equipped with jet skis, inflatable rafts and other equipment will be standing by at nearby Patrick Air Force Base and Joint Base Charleston in South Carolina for every commercial crew launch, on alert to mount a rescue mission if needed.

But to pull off a successful splashdown, the Crew Dragon used for the Demo 2 mission requires relatively light winds and mild sea states. Given the vast area that must be considered, that will be a tall order for weather officers normally focused on local conditions.

"Certainly, we do expect a higher risk of weather related scrubs on this mission," said Benji Reed, SpaceX director of crew mission management. "We need to think about the weather along the track of where Dragon can come back down. ... I would expect there to be a very high chance of scrub due to weather."

One NASA document said it could take up to 30 days to get the Crew Dragon cleared for launch given historical weather data for this time of year.

Catching up to the space station

But assuming an on-time launch and problem-free climb to space, Hurley and Behnken will check out the Crew Dragon's systems and take a few moments to test its manual control system before calling it a day. Catching up to the space station will be the flight computer's job. Approaching from behind and below, the Crew Dragon will loop up to a point directly ahead of the station with its nose aimed at a docking port on the front end of the lab's leading Harmony module where space shuttles once docked.

After another test of the capsule's manual controls, Hurley and Behnken will monitor an automated final approach and docking. Standing by to welcome them aboard will be space station commander Chris Cassidy and his Expedition 63 crewmates, cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner.

Hurley served as pilot of the shuttle Atlantis during the program's final flight in July 2011. His commander was Chris Ferguson, now a senior Boeing manager assigned to fly aboard back to the space station aboard the company's CST-100 Starliner commercial crew ship.

During the 135th and final shuttle flight, Ferguson and Hurley left an American flag aboard the station for retrieval by the next U.S. crew to visit. The flag was first launched aboard the shuttle Columbia during the orbiter's maiden flight in 1981.

"It was a good way to just say 'hey, the next time somebody flies something from the United States, this flag is going to be up here waiting for them,'" Hurley said. "I didn't think I was gonna fly again, let alone potentially be the guy that goes up and gets it. I mean, I still sometimes have a hard time believing it."

It will be the third visit to the space station for both Hurley and Behnken, veterans of two space shuttle assembly flights each.

They originally expected a one- to two-week test flight, but repeated commercial crew delays, and the presence of just one Soyuz-launched NASA astronaut aboard the station, prompted NASA to extend the mission.

Hurley and Behnken received extra training to help Cassidy with on-board research and Behnken, a spacewalk veteran, may join Cassidy for one or more high-priority excursions to install new solar array batteries and/or complete outfitting of a European experiment platform.

But it's not yet known how long the Crew Dragon mission might actually last. The longest the capsule assigned to Hurley and Behnken can remain in orbit is about 120 days due to predicted degradation of the Crew Dragon's solar cells from exposure to atomic oxygen in the space environment.

The actual performance of the arrays in orbit, along with forecasts for the offshore landing zone, will factor into the eventual return date. Whenever they come home, they'll have to contend with initial re-adaptation to gravity after splashdown while strapped into a bobbing crew capsule. It will be the first ocean landing for U.S. astronauts since the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project mission.

"Everybody's body is different coming back from space, you know?" Hurley said. "Some people do really well. And some people do pretty poorly, and then everything in between.

"The one thing we're certain of is water landings (are going to) exacerbate that to some degree. We'll just do the best we can. Bob and I do pretty well coming back (from space) normally. But, you know, it'll be a longer duration mission for both of us ... and landing in the water, it's not ideal. But that's just part of the process."

Commercial crew program critical for space station

NASA managers originally hoped to begin launching astronauts aboard SpaceX and Boeing commercial crew ships in 2017, ending the agency's sole reliance on the Soyuz and to assure the presence of up to four NASA and partner agency astronauts to carry out scientific research.

Anticipating the advent of U.S. commercial crew ships, Russia scaled back production of its three-seat Soyuz spacecraft and only two will be launched this year: the Soyuz MS-16/62S vehicle, which carried Cassidy and his two Russian crewmates into space April 9, and the second around October 14.

At the time of their launch, Cassidy's seat was the last one under contract to NASA. Since then, agency managers have negotiated one more seat aboard the Soyuz scheduled for launch in October.

And that's critical to NASA. At least one U.S. crew member must be aboard the station at all times to operate U.S. and partner agency equipment and systems. The additional Soyuz seat will assure a NASA presence through next spring even if the commercial crew program runs into major delays.

But the issue highlights the importance of a successful Crew Dragon mission.

"For 20 years we've had this space station crewed," Bridenstine said. "We need to make sure that we keep it crewed, and not just crewed, but we need to make sure that it has its maximum complement so we can get the highest return on investment. And that's what commercial crew is all about."

Since 2006, NASA has spent nearly $4 billion buying 70 seats on Russian Soyuz spacecraft, according to a report last November from NASA's Office of Inspector General.

Those numbers include 12 Soyuz seats NASA purchased since 2017, at a cost of about $1 billion, in large part because of delays in the Commercial Crew Program. The numbers do not include the cost of the recently negotiated seat that will be used in October.

But the Crew Dragon test flight goes well, NASA plans to launch three U.S. astronauts and one Japanese flier aboard the first operational Crew Dragon in the fall timeframe, joining Cassidy and boosting the NASA-sponsored presence aboard the station to five. They would remain in orbit for about six months and return to Earth next spring.

Boeing's CST-100 Starliner is expected to begin carrying astronauts to the station next year, after the company repeats a problematic unpiloted test flight later this year.

"It's been a long time since we've put humans on a brand new spacecraft," Bridenstine said at a briefing. "But that's what this is, and it is truly a test flight. Yes, they're going to go to the International Space Station and Bob and Doug are going to do amazing work while there. But we should not lose sight of the fact that this is a test flight. We're doing this to learn things."

"This is something they believe in"

SpaceX President and CEO Gwynne Shotwell reflected the feelings of many when she pointed at her neck during that same news conference and said "my heart is sitting right here, and I think it's gonna stay there until we get Bob and Doug safely back from the International Space Station."

"I think we have pounded the issues associated with Falcon and Dragon more than any other mission we've had in our in our history," she said. "We've also spent years working with the crew office and getting to know Bob and Doug.

"I wanted to make sure everyone at SpaceX understood and knew Bob and Doug, as astronauts, as test pilots — badass — but dads and husbands. I wanted to bring some humanity to this very deeply technical effort."

So do the crew's families.

"I would like people to realize that neither Bob nor Doug are people who seek the spotlight, they are doing this because this is something they believe in," Megan McArthur, Behnken's wife, told CBS News.

"I think it would be important for them to say that they're part of a large team that has all been involved in this effort for the last five years to get to this moment. They may be the most visible team members, but it's important to them to recognize that they're part of a team that's making this happen."

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiSmh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmNic25ld3MuY29tL25ld3Mvc3BhY2V4LWxhdW5jaC0yLW5hc2EtYXN0cm9uYXV0cy1jcmV3LW1pc3Npb24v0gFOaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuY2JzbmV3cy5jb20vYW1wL25ld3Mvc3BhY2V4LWxhdW5jaC0yLW5hc2EtYXN0cm9uYXV0cy1jcmV3LW1pc3Npb24v?oc=5

2020-05-25 12:06:56Z

52780800879773

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar