The long-awaited launch of NASA's next generational observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope, is just one month away.

The $9.8 billion Webb has overcome years of technical delays, funding issues and a pandemic to get to launch day in French Guiana, which is set for no earlier than Dec. 18.

Webb will have an ambitious science agenda stretching from studying small worlds in our solar system to surveying the outer reaches of the universe. "We're going to look at everything there is in the universe that we can see," Webb senior project scientist John Mather told reporters in a press conference on Wednesday (Nov. 18).

Related: Building the James Webb Space Telescope (photos)

"We want to know, How did we get here?" added Mather, who works at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. "The Big Bang, How does that work? We'll look, yes, and we have predictions. But we don't honestly know [how]."

Serving as the successor to NASA's venerable Hubble Space Telescope, Webb will journey to a distant destination about 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) from Earth known as a Lagrange point, a gravitationally stable spot between two celestial bodies.

It will take Webb a month to get there after launch. Then, the observatory will endure a six-month commissioning period that will include a variety of key milestones, from the unfurling of its complex mirror to ensuring that all instruments are working correctly, before Webb opens its eyes.

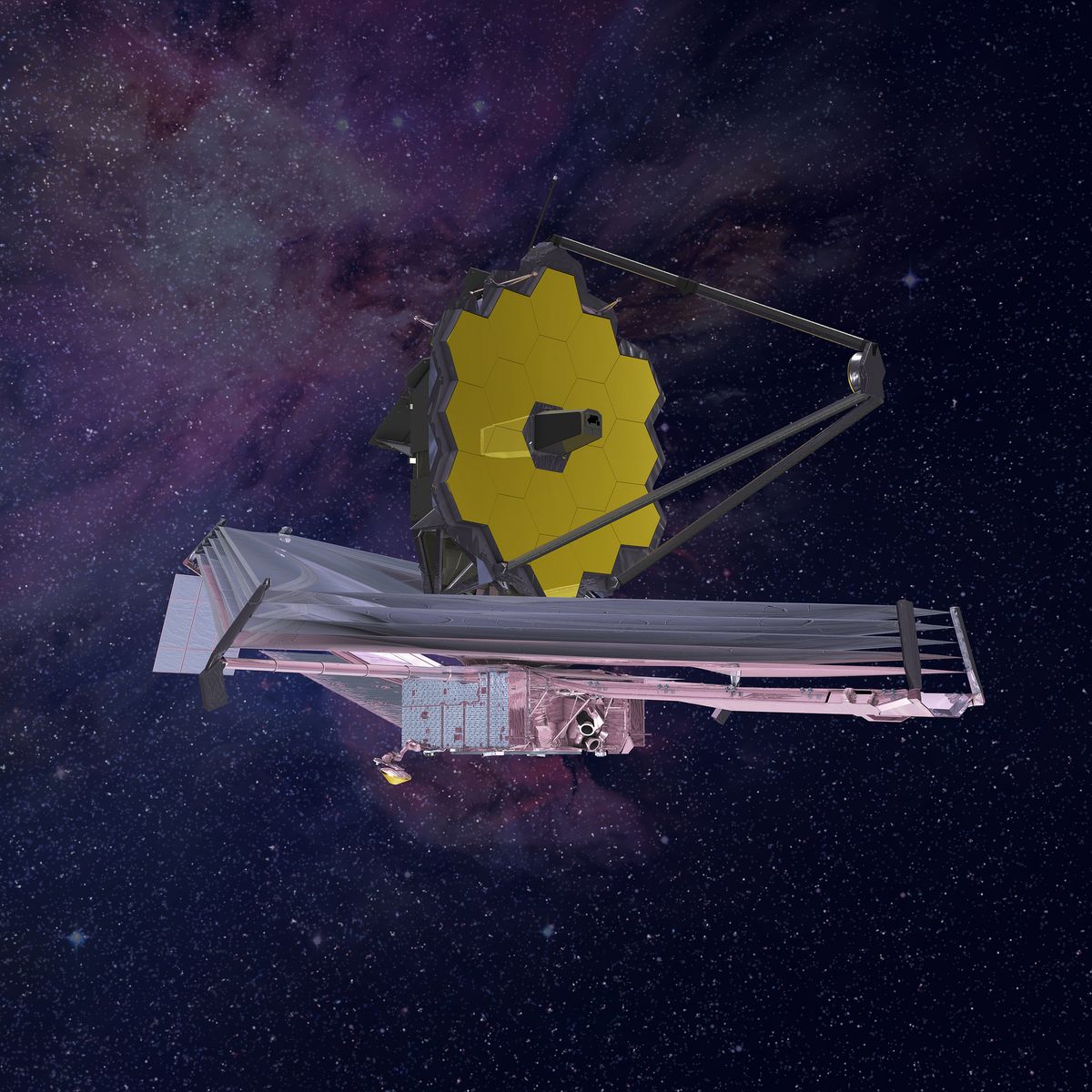

"At six and a half meters [21 feet], the primary mirror was too big to fit in a rocket, so we designed it so that would it would unfold in space," Lee Feinberg, Webb optical telescope element manager at Goddard, said during today's briefing. "It doesn't fold like a drop leaf table, so ... we needed mirrors that had to be in segments."

The mirrors, Feinberg added, initially act like 18 separate telescopes, and it will take algorithms several months to align them properly, to a precision of one-5,000th the diameter of a human hair. And that's assuming the telescope unfurls them all properly, which (despite years of testing and modeling) NASA has said is one of the biggest technical obstacles Webb will face.

Webb investigators are coy about what the telescope will focus on first once it's ready. But clues come from the list of "early release science programs" that will prioritize Webb's core science in the study of planets, the solar system, galaxies, black holes, stellar physics and star populations.

The first images will be in high demand, as mission scientists say the resolution will be 100 times better than that of Hubble and will reveal much more in infrared (or heat) wavelengths than the elder telescope can.

While the first targets have not yet been decided upon, Webb will soon be turning the clock back on observations of the universe, providing a look at the cosmos as it was just 100 million years after the Big Bang. Hubble has allowed scientists to peer back to 400 million years after the Big Bang, so Webb will fill a gap, Mather said.

Canada is providing a fine guidance sensor for pointing Webb, along with a spectrograph for examining exoplanets and galaxies. The nation receives a guaranteed 5% share of observing time for its contribution.

"One Canadian team will focus their studies on the atmospheres of exoplanets to determine their compositions and temperatures. Another Canadian team will study some of the first galaxies ever formed and galaxies gathered in dense neighborhoods called clusters," said Sarah Gallagher, an advisor to the Canadian Space Agency president.

Related stories:

What excites scientists most is the unpredictability of what Webb will reveal, and even a brief glance at Hubble history provides plenty of examples. At Hubble's launch in April 1990, no one knew of the existence of dark energy, a fundamental influence in cosmic expansion. Exoplanets also hadn't been confirmed yet, and yet today we know of thousands.

Hubble even found some surprises closer to home, such as when it helped NASA's New Horizons Pluto probe steer properly around some new discoveries. "Hubble discovered two new moons of Pluto that could help the New Horizons probe [navigate] the physics of that world a few years ago," said Klaus Pontoppidan, Webb project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. "We think Webb will would be no different in that sense."

Although launch day is always expected to induce butterflies, Greg Robinson, NASA's Webb program director, said he is confident the team will pull through to make these science discoveries a reality.

"We test as much as possible, as practical. We call it test as you fly," he said. "We tested the same way it's going to operate, based on a launch. And so we've done all of that, and I think we're in pretty good shape."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiRmh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnNwYWNlLmNvbS9uYXNhLWphbWVzLXdlYmItc3BhY2UtdGVsZXNjb3BlLWxhdW5jaC1vbmUtbW9udGjSAUpodHRwczovL3d3dy5zcGFjZS5jb20vYW1wL25hc2EtamFtZXMtd2ViYi1zcGFjZS10ZWxlc2NvcGUtbGF1bmNoLW9uZS1tb250aA?oc=5

2021-11-18 22:33:26Z

1130280847

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar