The launch of a cargo ship bound for the International Space Station was scrubbed at the last minute Sunday because of trouble with ground support equipment at the Virginia launch site, but engineers in Florida pressed ahead with plans to launch a $1.5 billion NASA-European Space Agency solar probe on an ambitious mission to give scientists their first views of the sun's poles.

"(It) will be the first time that we send a satellite out to take images of the sun's poles and in addition, getting the first ever data of the polar magnetic field," said Daniel Mueller, ESA project scientist with the Solar Orbiter mission. "We believe this really holds the keys to unraveling the mysteries of the sun's (11-year) activity cycle.

"We will also monitor the far side of the sun, which we cannot see from Earth, and combine that with data from satellites and ground-based telescopes to provide a full 3D view of our star. And so the orbiter is really a laboratory, we have a suite of 10 sophisticated instruments that we will (operate) together to track the evolution of eruptions on the sun from the surface out into space, all the way down to Earth."

The Solar Orbiter mission comes a year and a half after NASA's Parker Solar Probe was launched, a spacecraft that periodically flies through the sun's super-heated outer atmosphere, or corona, enduring extreme temperatures that rule out the use of sun-facing cameras.

Trending News

Instead, Parker's instruments are focused on studying the sun's complex electric and magnetic fields, the electrically charged particles making up the supersonic solar wind and the mechanisms that heat the corona to millions of degrees.

The Solar Orbiter will fly periodically inside the orbit of Mercury, within 26 million miles of the sun, facing temperatures higher than a pizza oven. But that's far enough out to enable cameras and telescopes, looking through "peepholes" in the spacecraft's heat shield, to capture what should be spectacular views.

Along with four instruments to study the solar wind, "we have six telescopes that observe the light from the sun in different parts of the rainbow spectrum," Mueller said. "Two of those are so called coronagraphs where we block out the light of the sun itself to image the faint emission of the environment around the sun, the so called corona.

"In addition, we have these sensors that measure, for example, ions in space. Elements on the sun are not only hydrogen and helium, but also sprinklings of heavier elements like iron, oxygen, neon. We measure those at the location of the spacecraft, we really weigh the particles, but we can also measure the light that they emit on the surface and thereby we have a unique way of linking the two."

If all goes well, the Solar Orbiter and the Parker Solar Probe will study the sun at the same time from different vantage points to help unravel some of the star's deepest mysteries.

"It's really a perfect dream marriage (made) in heaven," said Guenther Hasinger, director of science for the European Space Agency.

The Solar Orbiter mission cost roughly $1.5 billion, including the Atlas 5 rocket provided by NASA. The U.S. space agency also spent about $70 million building one of the spacecraft's instruments and other components, including a sensor that NASA's current science director, Robert Zurbuchen, helped design.

Launch of a flagship science mission like the Solar Orbiter normally would be center stage for NASA, but thanks to a few minor processing delays, the flight ended up on the same day NASA planned to launch another mission with important, if less lofty, ambitions.

And so, first up Sunday was a Northrop Grumman Antares 230+ rocket carrying a Cygnus cargo capsule loaded with 8,000 pounds of crew supplies, spare parts and science gear bound for the International Space Station. But unspecified trouble with ground support equipment triggered a scrub just three minutes from liftoff, and the flight was called off for the day.

The commercially-developed cargo ship is loaded with more than 2,000 pounds of science equipment — including the first scanning electron microscope carried to space — and another 1,700 pounds of crew clothing and other supplies, including two types of cheese, fresh fruit and even candy for Expedition 62 commander Oleg Skripochka, Drew Morgan and Jessica Meir.

"We do have some fresh fruits and vegetables packed up for the crew, ready for them, that's always a tasty treat," said Ven Feng, manager of NASA's space station transportation office. "This crew in particular had a couple of candy choices that they wanted, I don't know if that was for Valentine's Day or perhaps just their personal likes."

At the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, meanwhile, United Launch Alliance engineers readied an Atlas 5 rocket for launch at 11:03 p.m. Sunday to boost the Solar Orbiter spacecraft on an Earth-escape trajectory and a series of elliptical orbits that will carry the spacecraft within the orbit of Mercury.

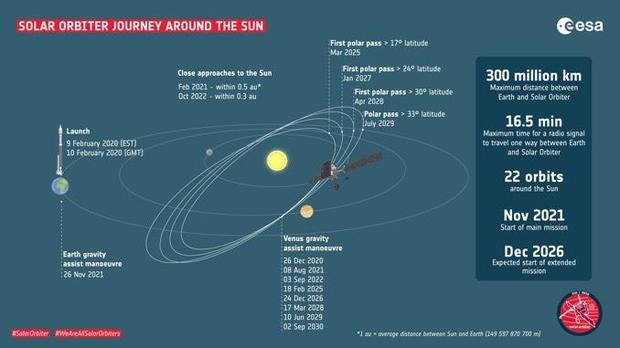

To get there, Solar Orbiter will fly past Venus in late December, using the planet's gravity to adjust its trajectory. After a second Venus flyby in August 2021, the spacecraft will whip past Earth the following November, setting up the third of eight planned Venus flybys through September 2030. Science observations will begin next year.

The gravity-assist flybys will eventually raise the tilt of the probe's orbit with respect to the sun's equator by about 35 degrees, allowing the spacecraft to "see" the star's polar regions. The first "polar pass" is expected in March 2025 when the Solar Orbiter reaches an inclination of 17 degrees.

"Solar Orbiter is special because it's really the first mission to try to link the sun to the heliosphere and establish a cause-and-effect relationship between what happens on the sun and what we observe in the near-Earth environment," Mueller said. "In particular, we want to find out in detail about how the solar magnetic field works.

"The only way to find out is to really fly to an altitude above the sun where we can look down on the sun's poles. And that's what we will do for the first time."

Zurbuchen said in an interview that studying the sun's polar regions and learning more about the fundamental physics of the "magnetic engine of the sun, the so-called dynamo," will lead to improved space weather forecasts and possibly even early warning of potentially destructive solar flares and coronal mass ejections that can play havoc with power grids, communications and navigation.

"It's like your hurricane season," he said. "There's going to be a forecast sometime this year that says this hurricane season it's going to be nominal, super strong and so forth. So that comes from observations of ocean temperature, from flows and so forth. We think the ingredients of the solar cycle are in the polar regions. We think if we understood that, we could predict that on a macroscopic level."

Bottom line: "We would expect that in 10 years we have a substantially better understanding of how to predict, to model space weather, to look at the signs, the signature of the solar surface in a way that we can use it to improve models."

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiaWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmNic25ld3MuY29tL25ld3MvZXVyb3BlYW4tc29sYXItb3JiaXRlci1wcm9taXNlcy1maXJzdC1sb29rLWF0LXN1bnMtbXlzdGVyaW91cy1wb2xhci1yZWdpb25zL9IBbWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmNic25ld3MuY29tL2FtcC9uZXdzL2V1cm9wZWFuLXNvbGFyLW9yYml0ZXItcHJvbWlzZXMtZmlyc3QtbG9vay1hdC1zdW5zLW15c3RlcmlvdXMtcG9sYXItcmVnaW9ucy8?oc=5

2020-02-10 00:00:00Z

52780592858155

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar