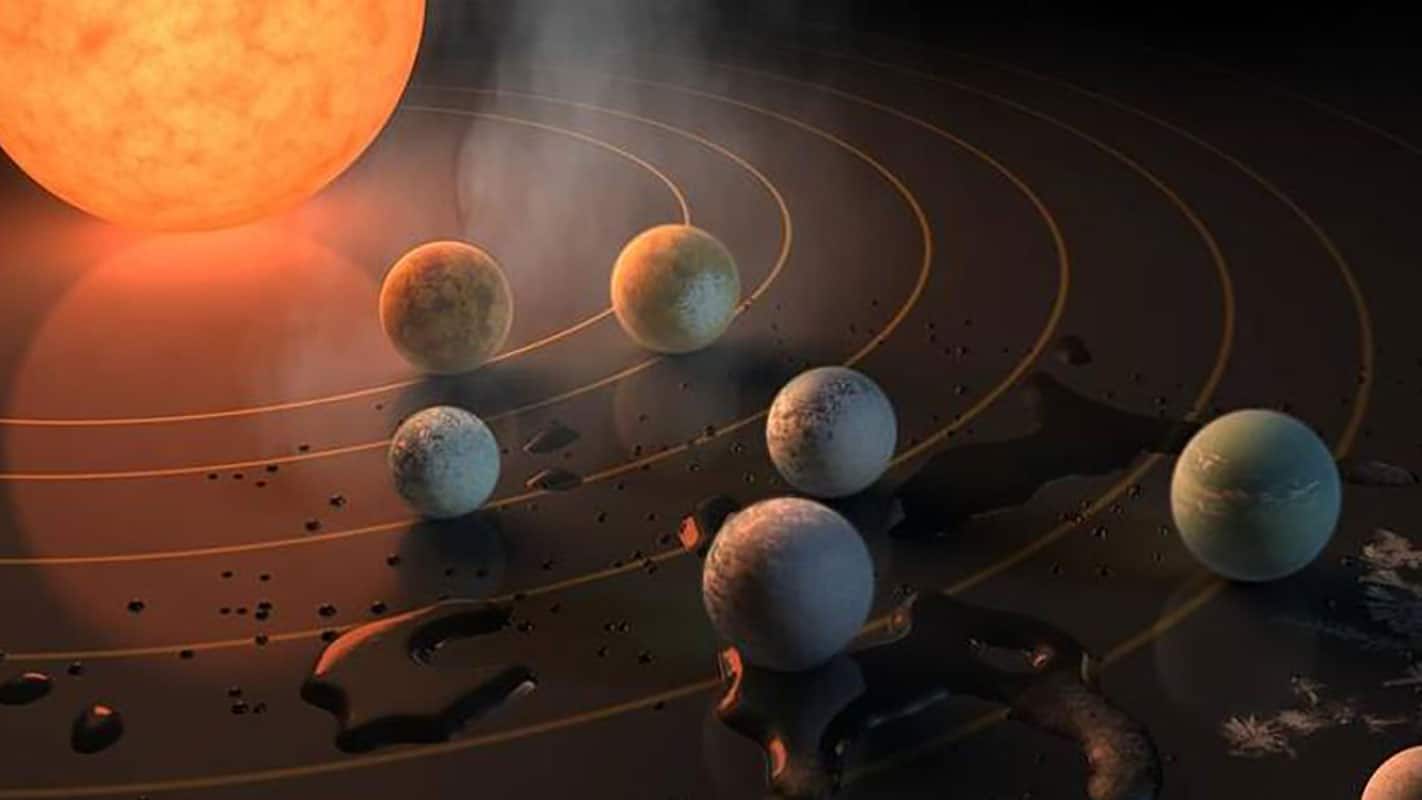

To date, over 5000 exoplanetary systems have been discovered. Biosignatures are chemical components in a planet’s atmosphere that may indicate life, and they frequently include abundant gases in our planet’s atmosphere.

Scientists at UC Riverside suggest something is missing from the typical roster of chemicals astrobiologists use to search for life on planets around other stars — laughing gas.

Eddie Schwieterman, an astrobiologist in UCR’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, said, “There’s been a lot of thought put into oxygen and methane as biosignatures. Fewer researchers have seriously considered nitrous oxide, but we think that may be a mistake.”

To reach this conclusion, scientists determined how much nitrous oxide a planet like Earth could conceivably produce. After that, they created simulations of that planet orbiting various types of stars and calculated the amounts of N2O that could be captured by a telescope like the James Webb Space Telescope.

Nitrous oxide, or N2O, is a gas produced in various ways by living things. Microorganisms continuously convert other nitrogen molecules into N2O through a metabolic process that can produce useful cellular energy.

Schwieterman said, “Life generates nitrogen waste products that are converted by some microorganisms into nitrates. In a fish tank, these nitrates build-up, which is why you have to change the water. However, under the right conditions in the ocean, certain bacteria can convert those nitrates into N2O. The gas then leaks into the atmosphere.”

N2O can be found in an environment and still not be an indication of life in some situations. This was considered in the new modeling. For instance, lightning can produce a small amount of nitrous oxide. However, lightning also produces nitrogen dioxide, giving astrobiologists a hint that non-living meteorological or geological processes produced the gas.

Others who have considered N2O as a biosignature gas often conclude it would be difficult to detect from so far away. Schwieterman explained that this conclusion is based on N2O concentrations in Earth’s atmosphere today. Because there isn’t much of it on this planet, which is teeming with life, some believe it would also be hard to detect elsewhere.

Schwieterman said, “This conclusion doesn’t account for periods in Earth’s history where ocean conditions would have allowed for the much greater biological release of N2O. Conditions in those periods might mirror where an exoplanet is a today.”

“Common stars like K and M dwarfs produce a light spectrum that is less effective at breaking up the N2O molecule than our sun is. These two effects combined could greatly increase the predicted amount of this biosignature gas on an inhabited world.”

The study was conducted in collaboration with Purdue University, the Georgia Institute of Technology, American University, and the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Journal Reference:

- Edward W. Schwieterman, Stephanie L. Olson et al. Evaluating the Plausible Range of N2O Biosignatures on Exo-Earths: An Integrated Biogeochemical, Photochemical, and Spectral Modeling Approach. The Astrophysical Journal. DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac8cfb

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiQWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnRlY2hleHBsb3Jpc3QuY29tL2xhdWdoaW5nLWdhcy1zcGFjZS1tZWFuLWxpZmUvNTQxNDMv0gEA?oc=5

2022-10-06 10:22:38Z

1586268591

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar